Wuhan

In my experience, Wuhan (and its province, Hubei) is often looked upon even in China as something of a culinary and cultural backwater. Among many circles, it is known for somewhat coarse or aggressive residents, brutally hot weather in the summer months, and a chaotic approach to economic development. Some of my friends from Wuhan have often lamented their relegation to this second tier of existence, complaining that their city does not get its fair share of recognition.

Now, of course, it has achieved global fame as the epicenter of humanity’s most recent global pandemic, which I suspect is not exactly the kind of recognition they were seeking.

Because of this newfound notoriety, people have formed quite a lot of opinions about Wuhan recently, quite a lot of which they aren’t shy to share on social media or on various national stages. While I am entirely unqualified to comment on politics or healthcare, I do love to eat and cook. One of the ways I come to love a place or people is through its food, and Wuhan remains particularly close to my heart. In that respect, I think I can introduce an alternate perspective.

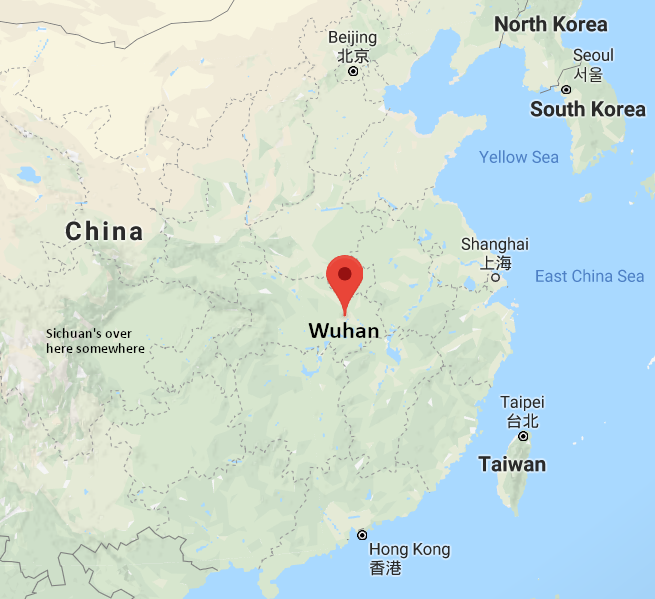

Wuhan’s cuisine very much reflects its location astride the Yangtze river, almost exactly halfway along the river’s meandering route from Chongqing (and Sichuan) in the west, to Shanghai in the east. Historically, it has been a trade and transportation hub that links western and central China to eastern China, and offered goods and produce from its surrounding provinces to the rest of the world.

As a result, it has had access to an unusually wide variety of produce, spices, and cooking techniques. This has led to something of a mongrel cuisine that can be somewhat hard to pin down, but draws its roots from a number of other, more distinct traditions. Much like Singapore, Hong Kong, and Vietnam, this has led to a number of local dishes that are unique to the area, and that try to blend the best of their worlds together into one bowl.

Throughout Wuhan’s cuisine you will see hints of flavors and traditions from any and all of the following:

- Sichuan: Famous the world over for its “numbing hot” flavor profile, which makes liberal use of Sichuan peppercorns, dried chilies, flavored oils, and a bewildering array of spices and cooking techniques.

- Shanghai and Jiangsu: Known for noodles, dumplings, and a much sweeter flavor profile than the rest of China, with sugar and vinegar taking a prominent role in many dishes.

- Hunan: Hubei’s (and Wuhan’s) neighbor to the south, Hunan is famous for a “fragrant spicy” flavor profile, which is characterized by ferociously hot chilies, pickled and dried produce of all sorts, and heavily smoked and salted meats and fish.

- Western China and the Mediterranean: As a major stop along the spice trade routes of old, you’ll see quite a lot of spices like cumin, and a tradition of heavily spiced meats, fish, shellfish, and produce grilled on skewers.

I often find that many of my favorite foods arise in places, and from traditions, that have historically been sidelined. Wuhan is just such a place; flavors and temperaments there have yet to be softened by tourists’ taste buds or the niceties of international commerce.

That said, in my experience, much like their food, the sometimes rough and fiery attitude of some of Wuhan’s people is usually tempered by a genuinely tender, even sweet sense of sympathy and fairness.

Comments ()